How Private Equity Gets Paid

Inside Private Equity: Understanding a Fund Model

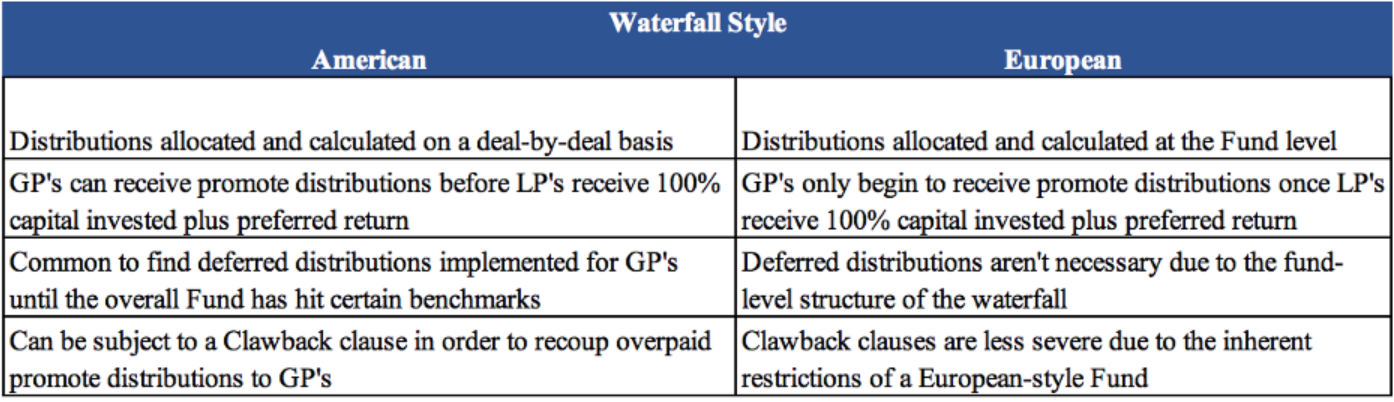

American vs European Waterfall Structures

When dealing with a fund, one of the most important aspects is the distribution method. Private equity firms typically allot the money from an investment based on a distribution waterfall model, which is a method of disproportionately allocating distributions to the Limited Partner (“LP”) and General Partner (“GP”). Instead of the distributions being allocated pro-rata based on the ownership percentage, the distribution waterfall allows for the distributions to be made based on other calculations. There are two types of distribution waterfall structures: American and European. The specifics of the Distribution Waterfall mechanics are typically detailed in the distribution section of the Limited Partnership Agreement (“LPA”).

An American-style distribution waterfall is applied on a deal-by-deal basis and is typically more beneficial for the GP. Because it is applied on a per deal basis, deal performance is independent of other deals in the fund, from a promote standpoint. An American-style distribution waterfall favors the GP as it allows them to receive promote distributions before the LPs have received their entire capital back plus a specified preferred return.

American-style distribution waterfalls will require that LPs only earn capital back and preferred return for the specific deal the distributions are coming from. For instance, let’s take a distribution waterfall with 4 tiers: (i) 100% LP until they receive Capital back plus 8% preferred return; (ii) 90% LP / 10% GP until the LPs achieve a 10% IRR; (iii) 80% LP / 20% GP until the LPs achieve a 14% IRR, and (iv) 70% LP / 30% GP thereafter. In an American-style fund, the GP could start to receive their disproportionate share of the distributions before the LPs have received their capital back plus 8% on the entire portfolio, so long as they have achieved their capital back plus 8% on the equity invested in the distributing investment and other sold investments.

On the other hand, a European-style distribution waterfall is applied at the fund level and tends to be more beneficial for the LP. Under the European style, the GP will not receive promote distributions of any kind until all of the LP’s capital contributions have been repaid and their preferred rate of return has been reached.

Because of this, it is possible for the GP to wait years to receive their promote distributions (~6 years on average for a European-style closed-in fund with a 10-year investment term).

If a fund performs well, then the GP would likely still receive the same % of profits in either an American or European-style fund. However, the American style would pay the GP earlier. When a fund reaches mid-tier returns or lower, then the American style could still see the GP receiving promote distributions even if the fund achieves negative returns, which would not happen in the European style waterfall.

Investment Period

The investment period of a fund is a set period after raising capital, generally 3-4 years, that the fund can freely invest the raised capital into assets. During the investment period, management fees are usually charged and calculated based on committed capital. After the investment period, fees are usually calculated based on the fund’s invested capital in non-disposed deals. For example, a fund in the investment period with $100MM of capital charging a 1.5% management fee could take a $1.5MM fee based on the committed capital. However, after the investment period is over, the fund has invested $75MM but sold $25MM of their investments. Since the investment period is over, the fund can only charge on the invested capital outstanding. Thus, the fund could only receive $750,000 (1.5% x ($75M-$25M)).

The fees charged during the investment period are one of the reasons for the notorious j-curve: the j-shaped trend line for a fund’s IRR. Typically, the returns for a PE fund are negative for the first couple of years and then positive thereafter. With the investment period, funds are charging fees on capital that has not yet been invested. Thus, the IRR during this time is infinitely negative because you are paying fees but receiving no returns or distributions. You are completely cash flow negative. Likewise, early deal performance can appear to suffer due to bearing the entire brunt of the Fund’s investment period expense load.

One aspect that should not be confused is how the management fee is calculated. The management fee is calculated based on the equity one has in the deal, not the fair value of the investment. So when fund managers have a deal that isn’t going well and they write down the fair value of the investment to $1, the LP would still have to pay management fees based on the amount of equity in the deal.

The same goes for vice versa. If the fund manager had a high-performing investment and writes up the fair value, you are not going to pay more in fees simply because the value of the investment went up. The fees are entirely based on the equity in the deal and not the fair value.

Allocation of Management Fees

The method in which the fund allocates management fees across their investments can have a large effect on the distributions made to the GP. Fund managers can either allocate fees at the fund level, or on a per deal basis, and these management fees generally range from 1% to 1.5% of the assets under management.

If the fund allocates fees at the fund level, it will come at a cost to the IRR. For instance, a $100MM fund invests in their first deal for $10MM and charges 1.5%. Right off the bat, the investors will be charged $1.5MM in fees on their first deal. This essentially wipes out any potential distributions that the LPs were hoping to pocket and demolishes their initial IRR.

But, if you allocate fees on a per deal basis you will continue paying fees over a longer period of time, but your individual investment IRRs will be more consistent compared to the other investments. The fee is allocated based on called capital, so Funds will generally allocate fees across deals based on the proportion of capital used in the deal. For example, if you used 20% of your total capital for a deal, you would charge 20% of your total fee to that deal. However, allocating fees on a deal-by-deal basis also has its downsides. One main downside is the accrual of fees and expenses for later deals and its effect on the distributions. For instance, imagine you have 10 deals over 4 years. Deals 1-9 deals were invested in year 1, and deal number 10 was invested in year 4. In this case, deal 10 will have to perform at a higher level for its distributions to make it through the waterfall tiers. This is because deal 10 has to bear its share of years 1-3 expenses, even though it was not yet invested. Although a clear impediment to deal 10’s performance, this method is used to minimize the effects of the j-curve. It is better to have later deals bear their portion of early expenses, at a slight negative to IRRs, than have early deals bear the entire portion with massive penalties to their IRR.

Clawback Clause

A Clawback is a feature detailed in the LPA that refers to the LPs right to recoup cashflow previously distributed to the GP. A clawback is common in American-style waterfalls and is calculated upon liquidation of the fund. Clawback provisions play a key role in protecting the LPs from overpaying incentive fees to the GP. For example, in the American-style waterfall the GP could begin receiving distributions before the LPs had reached their required investment return hurdles. Let us say the GP takes a promote distribution and over the life of the Fund, it turns out the later deals in the Fund aren’t as successful as the initial deal, and the LPs never receive their entire capital back. Thanks to the clawback feature, the LPs are entitled to reclaim the promote they overpaid to the GP. However, one thing to note is that the clawback feature is only as good as the fund manager’s ability to repay. Many LPAs will require a portion of promote be deposited into escrow accounts to ensure that at least a portion of promote is easily recoverable in the clawback clause is exercised.

Deferred Distributions

If you are in an American-style waterfall model, deferred distributions will most likely be a constant theme when dealing with promote distributions. A deferred distribution is, as the name suggests, when a distribution to the GP is delayed. Since American-style waterfall models are on a per-deal basis, the GP can receive a promote distribution on the first deal after the LPs hit their hurdles for the specific deal. Usually the LPs do not want the GP cashing out on all their deals up front without guaranteeing the performance of later deals, so the fund will defer 40%-60% of the earned promote distributions until the fund as a whole reaches capital back plus preferred return. Additionally, distributions can be deferred 100% if it does not appear that the fund will return the capital plus preferred return to the LPs based on a hypothetical liquidation using the current fair value of the assets.

Investors in European-style funds will not encounter deferred distributions due to the fund-level structure of the European waterfall. In the European-style waterfall, the GP only receive a promote distribution after the LPs receive all of their capital back plus a preferred return.